Market Update: PPI Pullback and the ‘New Normal’ for Inflation

Judging by capital market expectations, we are over the hump. The global inflation crisis of the last year-and-a-half has peaked, and price increases are now expected to trend downward in the US, UK and Europe. US Treasury yields have fallen consistently since the beginning of November and are now back to where they were in September – just before the world had a UK-inspired bond rodeo. This implies lower growth and price expectations in the years ahead, and comes on the back of a 6.5% December annual inflation reading in the US – its lowest in more than a year.

It is worth remembering that the world has been in a “bad news is good news” stage of its economic cycle (as slowing growth will take the pressure off central banks’ to keep raising rates) – at least this has been the market’s perception over the last few weeks. With central banks tightening hard and fast across the developed world, investors are looking through the pain of this cycle to the joys of the next one, perhaps assuming this pain may turn out to be minor and quite short lived. The sooner this one ends the better, and so signs of economic weakness are welcomed by markets. Lower inflation readings are backed up by both easing supply constraints and notably weaker demand. Global demand has slowed substantially, easing public pressure on central banks to bring demand-driven inflation down.

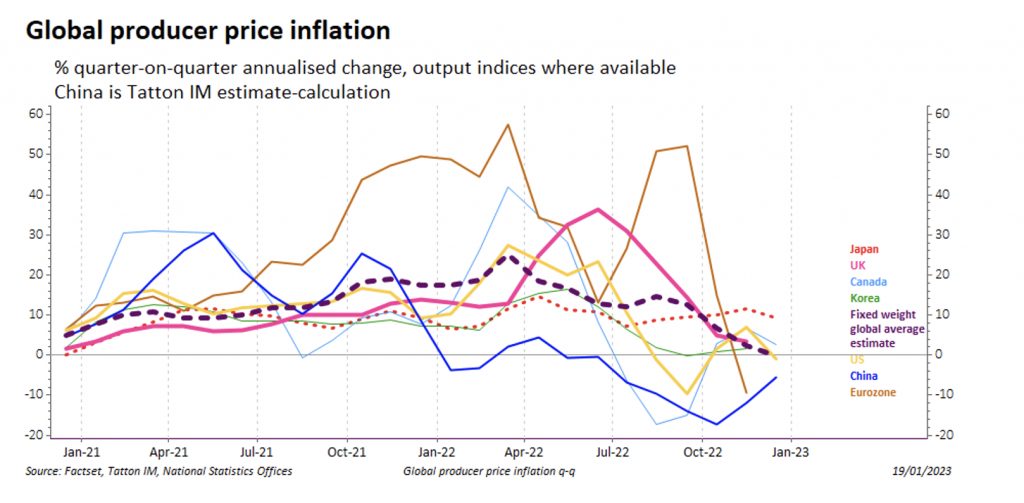

Of particular note is the fall in producer price inflation (PPI). While it mirrors and starts with commodity price changes, it also more tightly reflects businesses’ pricing power across the whole value chain. It is therefore seen as a good indicator of the supply-demand balance. The chart below shows quarterly changes (annualised) in PPI over the last year for a few major world economies. As we can see, producer inflation is trending consistently down in most regions – particularly Europe – and has been for the last few months. The one exception is China which, after years of repeated lockdowns, finds itself only at the very beginning of the same recovery cycle that pushed up prices in other regions since the spring of 2021. All the same, Chinese PPI is starting from a much weaker position, deeply negative.

While the Covid-induced price shock that triggered this exceptionally strong run of elevated inflation is therefore turning into a diminishing issue, the US Federal Reserve (Fed), along with its peers, sees the prevention of a destructive wage-price spiral as their new priority. Therefore, central banks remain committed to tightening policy in spite of a weakening economy. Nevertheless, these PPI figures point to a very different scenario. Far from entrenched inflation, it looks like the US backdrop became disinflationary around September, and has stayed that way into the new year.

In that time, global demand and price pressures have eased greatly. Energy prices – particularly for wholesale natural gas – have fallen substantially since November on the back of a much warmer winter than expected. Even Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey – a committed hawk in the global inflation fight – has admitted this makes the job much easier. He is now optimistic about an “easier path” out of inflation pressures.

Capital markets are buying into this optimism, but not everyone is convinced. Christian Ulbrich, chief executive of global real estate firm JLL, told the Financial Times this week from the Davos World Economic Forum that “fundamental trends” mean “inflation will stay persistently around 5%”. This is reportedly a view shared by many of the movers and shakers in Davos, and it backs up commentary we are seeing quite widely in the financial media.

There is an emerging view that the old regime of 2% average inflation is gone, and will be replaced by an average much closer to 4% over the long-term. The thought is that, due to structural changes in the global economy, central banks will no longer feasibly be able to target 2% inflation and will have to adjust their targets higher. This will mean structurally higher interest rates too – a far cry from what we saw in the period between the global financial crisis and the pandemic.

The long-term factor that most strongly drives this view is globalisation, or lack thereof. Since the 1980s, economies have become increasingly interconnected, putting a structural downward pressure on prices by increasing the available supply of goods and thereby indirect access to much cheaper labour. That process no longer looks guaranteed, and is arguably going into reverse. This is partly due to longstanding political grievances which are delivering more protectionist politics, and partly due to concerns over supply chain security. Trump’s trade wars and Brexit are an example of the former, while Europe’s move away from Russian gas is an example of the latter.

US-China trade tensions are a clear example of deglobalisation, but prospects for reconciliation have improved substantially in the last month or so. That brings us to the next corollary, however: China’s integration to the world economy over recent decades has been a structural force holding inflation back. In simple terms, this was due to the cheapness of producing goods in China versus elsewhere.

This is no longer the case. Wages and production costs have increased dramatically in the world’s second-largest economy, to the point where China is no longer a deflationary force. Quite the opposite, in fact, as strong Chinese growth generates demand for commodities. Now, when China goes on a growth binge, it puts upward pressure on global input costs.

This is certainly an upward force on global inflation, but whether this translates to structurally higher inflation in the long-term is another matter. On that front, we can only point out that moving to a regime of 4% annual inflation is not a simple matter. Inflation disproportionately affects lower income earners by destroying their purchasing power. To counteract this, the economy has to give disproportionate wage increases to the less well-off, or else inequality grows dramatically, with potentially disastrous political consequences.

That is fine as an economic model; it is how most western economies operated from the end of the second world war up to the 1970s, a period of great improvement in living standards. But it means that returns to labour outpace returns to capital – which in turn means a structural barrier to equity market growth. Again, none of this is necessarily a bad thing – especially if it creates a more dynamic underlying economy with more growth from growing consumer demand – but investors have to recognise what a 4% annual inflation regime would mean. Davos attendees should be careful what they wish for.

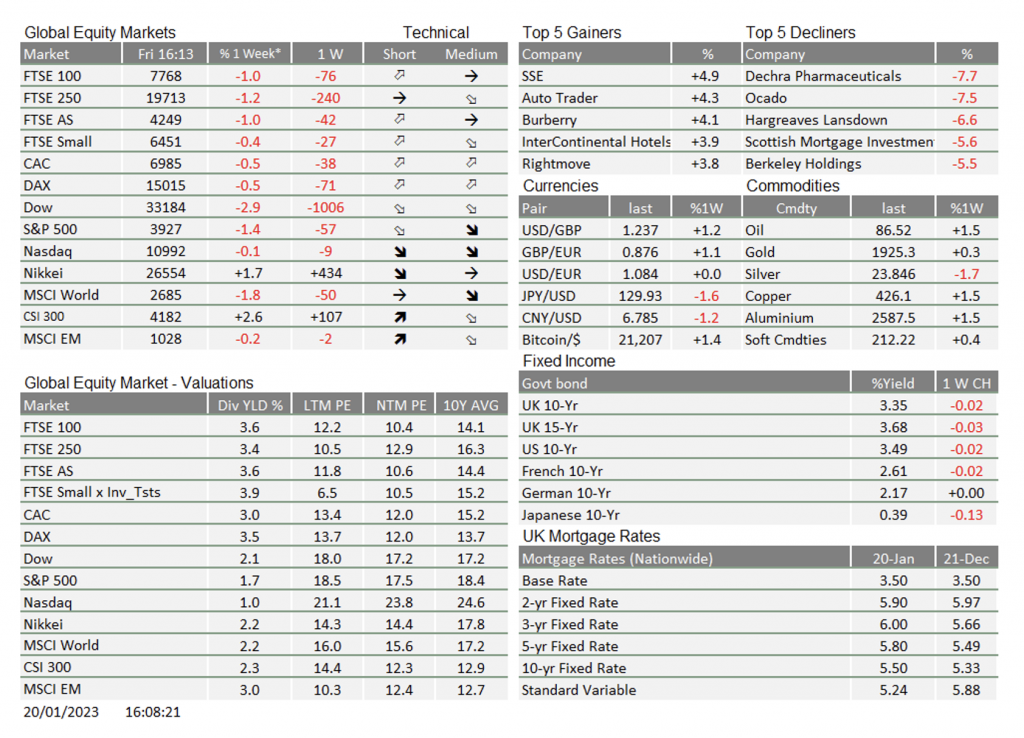

* The % 1 week relates to the weekly index closing, rather than our Friday p.m. snapshot values

** LTM = last 12 months’ (trailing) earnings;

***NTM = Next 12 months estimated (forward) earnings

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

This week’s writers from Tatton Investment Management:

Lothar Mentel

Chief Investment Officer

Jim Kean

Chief Economist

Astrid Schilo

Chief Investment Strategist

Isaac Kean

Investment Writer

Important Information:

This material has been written by Tatton and is for information purposes only and must not be considered as financial advice. We always recommend that you seek financial advice before making any financial decisions. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.

Reproduced from the Tatton Weekly with the kind permission of our investment partners Tatton Investment Management

Who are Vizion Wealth?

Our approach to financial planning is simple, our clients are our number one priority and we ensure all our advice, strategies and services are tailored to the specific individual to best meet their longer term financial goals and aspirations. We understand that everyone is unique. We understand that wealth means different things to different people and each client will require a different strategy to build wealth, use and enjoy it during their lifetimes and to protect it for family and loved ones in the future.

Our approach to financial planning is simple, our clients are our number one priority and we ensure all our advice, strategies and services are tailored to the specific individual to best meet their longer term financial goals and aspirations. We understand that everyone is unique. We understand that wealth means different things to different people and each client will require a different strategy to build wealth, use and enjoy it during their lifetimes and to protect it for family and loved ones in the future.

All of us at Vizion Wealth are committed to our client’s financial success and would like to have an opportunity to review your individual wealth goals. To find out more, get in touch with us – we very much look forward to hearing from you.

The information contained in this article is intended solely for information purposes only and does not constitute advice. While every attempt has been made to ensure that the information contained on this article has been obtained from reliable sources, Vizion Wealth is not responsible for any errors or omissions. In no event will Vizion Wealth be liable to the reader or anyone else for any decision made or action taken in reliance on the information provided in this article.