Market Update October: The state of the global economy

By most measures, economic growth has been disappointing over the last few months. Economists started the year with high expectations for the post-pandemic recovery to become a sustained expansion – optimistic that vaccines and rebounding confidence would spur activity. The hope was that COVID conditions would normalise while monetary and fiscal policy remained supportive, leading to a virtuous growth cycle with higher wages, credit growth and global demand well into 2022. Quite a few economists were even worried demand could prove too strong and cause rapid and damaging inflation. And even though most would have expected a slowdown in the second half of this year, a few factors did not quite turn out as expected in the summer and autumn months.

By most measures, economic growth has been disappointing over the last few months. Economists started the year with high expectations for the post-pandemic recovery to become a sustained expansion – optimistic that vaccines and rebounding confidence would spur activity. The hope was that COVID conditions would normalise while monetary and fiscal policy remained supportive, leading to a virtuous growth cycle with higher wages, credit growth and global demand well into 2022. Quite a few economists were even worried demand could prove too strong and cause rapid and damaging inflation. And even though most would have expected a slowdown in the second half of this year, a few factors did not quite turn out as expected in the summer and autumn months.

Inflation expectations came true, in a sense. Prices for many goods have picked up substantially across the developed world – led by a sharp uptick in the cost of energy. But the latest spikes have been driven more by heavy supply constraints than rejuvenated demand. Oil and gas prices have risen substantially on the back of tighter supply, while labour shortages in delivery have exacerbated the problem and caused knock-on effects for a host of other goods.

To be clear, inflation itself is not always a bad thing. Much of the excitement investors felt in January was driven by the so-called ‘great reflation’ trade, when optimism and policy support was expected to drag the developed world out of the sluggish decade leading up to the pandemic. Price rises can be a spur of real (inflation-adjusted) growth. But that tends to come from higher disposable incomes and more confident consumers – while sudden price spikes can have the opposite effect.

Britain is a case in point. The Bank of England (BoE) now expects inflation to hit 4% or more by the end of the year. And while some of this comes from sharp wage increases in understaffed industries (like much-needed lorry drivers, who have reportedly seen wages rise as much as 15% this year) most people’s incomes have not risen nearly as much. The BoE reports that typical pay settlements are around 2-3% higher than a year ago. With prices rising and taxes set to increase, the average Briton has seen their real income fall.

Similar trends can be seen in the US and Europe. Global supply shortages have pushed up prices but without a comparable increase in short-term growth prospects, meaning many consumers and businesses will see themselves as worse-off – putting a dampener on demand. These fears have been heightened by media talk of 1970s style ‘stagflation’, where prices continue to rise despite low growth. If that came true, it would mean an end to the post-pandemic growth cycle before it properly began.

Fortunately, we do not expect that to happen, as slowdowns driven by supply issues – as long as they remain temporary – have proven much less difficult to remedy than demand shortages. Given the focus had as usual been on demand, the economy hit an unexpected air pocket over the summer, but it is still in flight. The slower-than-anticipated unwind of supply constraints and concerns over the Delta variant mean the rough patch will likely spill over into the fourth quarter. However, these problems are unlikely to persist into the medium term, given global production resources for goods are merely ‘out of kilter’ following the abrupt restart, but still have the same capacity as before the pandemic (when oversupply tended to be the economic worry point). This is not withstanding the longer-term structural change we can see in the ‘green transition’ of global capital allocation leading to continued elevated prices for much needed input materials of ‘old’ but still very much needed manufacturing sectors (for instance metals and minerals – we wrote previously about this).

In terms of COVID, the UK’s recent experience has shown variant-driven outbreaks in highly vaccinated populations are not a systemic threat, while vaccine rollouts have lessened the need for lockdowns even in developing countries. Those two points together mean supply issues should clear up soon enough – just as the UK-EU vaccine spat did after vaccine suppliers increased production.

To put it bluntly, the current problems are somewhat old news for investors, even though they may persist a bit longer. For the cycle as a whole, underlying fundamentals remain strong. Household balance sheets are in good shape, supported by surplus savings built up during lockdowns, which will help households to absorb temporary price rises in energy and food. On the business side, companies reliant on high yield corporate (junk) bonds in the US, which can always be a bit of a soft spot, have pushed their debt maturity into the future, meaning they are less vulnerable to rising interest rates. The three major developed market central banks – the US Federal Reserve (Fed), European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of Japan (BoJ) are unlikely to raise interest rates into the current cost inflation shock, even if some of the Fed’s representatives have sounded a bit more nervous about the persistence of inflation. The underlying reasoning being that tighter policy would drive down demand but do little to counter supply constraint-driven price pressures. And of course, a lot of focus is on so-called ‘second round’ effects. Here, the debate hinges on whether there is sufficient evidence that higher commodity prices are persistently driving up wages across sectors, without at the same time triggering productivity, increasing business investment.

Fiscal policy will tighten everywhere when compared to the extraordinary COVID stimulus boost, but the US and Europe have both put forward substantial infrastructure support packages. They are not always a ‘given’ in a normal cycle, and hence should be viewed as a incremental positive, especially in comparison to the aftermath of the global financial crisis, when many governments did the exact opposite by very quickly switching to fiscal austerity. Interest rates are low, and the combination of a demand surplus and undersupply provide a double incentive for productive investment – all the ingredients for a cyclical pick-up in growth.

Admittedly, some of the positivity from January seems overly optimistic now. There was hope that consumer savings built up over the pandemic would become a significant, if not worrying source of demand and growth once confidence improved. That now looks less uncertain, as on the one hand the demand is not being met by sufficient supply, and on the other, many individuals have dropped out of the labour market altogether – especially in the US – and so will be more eager to maintain their savings. The lower labour participation rate could push up wages over the medium- term, but we are still waiting on labour market tightness to feed through into increased consumer confidence/consumption and business investment.

In the meantime, spiking global inflation makes things difficult for emerging markets (EMs). EM central banks do not have the luxury of waiting out the inflationary storm like their DM counterparts. Many have had to tighten monetary policy this year, choking off growth while their economies are still reeling from Delta outbreaks. A loosening of global supply problems will be crucial for EM prospects, alleviating cost pressures and allowing policymakers to ease conditions. If global activity improves and the Fed maintains its loose monetary stance, we should also see downward pressure on the US dollar – a factor that almost always benefits EMs.

The elephant in the room throughout all of this is China. The world’s second-largest economy has been one of its main sources of incremental growth for over a decade, and many expected this to continue after the pandemic. But the recent troubles in the property market – and extensive interventions from the Chinese government – have put that in doubt. Evergrande, one of China’s biggest property developers, is teetering on the edge of a collapse, which could put serious pressure on domestic Chinese growth, even if it does not pose a systemic risk to global financial markets, as some had been quick to suggest.

We still do not expect a so-called ‘Lehman moment’ ahead for Evergrande and China, but the response of the Communist Party had initially not been encouraging. President Xi Jinping appears eager to use the current crisis as a means of driving forward his agenda – on everything from systemic deleveraging, re-enforcing the caveat emptor (buyer beware) principle among Chinese property punters to making housing more affordable under his drive towards common prosperity. Not all of this is a negative for China’s long-term growth prospects, but enough of it is. What’s more, the short-term damage this policy drive could do to confidence and investment are a threat to the fragile global growth cycle.

Ultimately, we should expect Beijing to avoid excessive contagion where they can, given only high growth rates are conducive with Xi’s overarching aim of creating a more evenly prosperous society in China. But Chinese policy is another hurdle the world will have to overcome if strong growth is to return (hence the very positive market reaction this week to the decisive policy action mentioned in this week’s top article). Like the other risks, it does not detract from the underlying strong fundamentals – although perhaps this area has the potential to make a bigger impact on next year’s growth outlook than the supply chain issues currently keeping observers of the western world occupied.

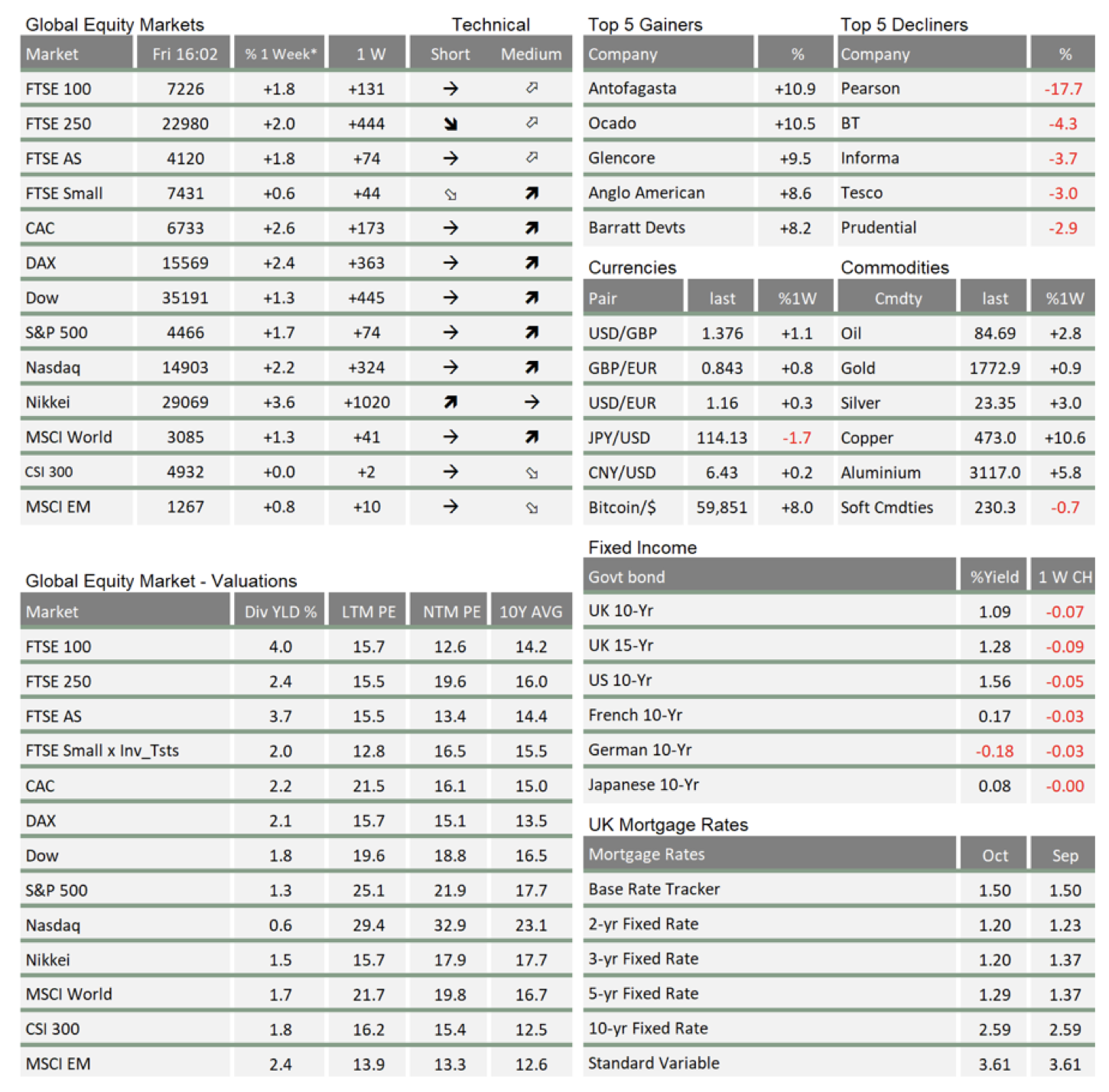

* The % 1 week relates to the weekly index closing, rather than our Friday p.m. snapshot values

** LTM = last 12 months’ (trailing) earnings;

***NTM = Next 12 months estimated (forward) earnings

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

This week’s writers from Tatton Investment Management:

Lothar Mentel

Chief Investment Officer

Jim Kean

Chief Economist

Astrid Schilo

Chief Investment Strategist

Isaac Kean

Investment Writer

Important Information:

This material has been written by Tatton and is for information purposes only and must not be considered as financial advice. We always recommend that you seek financial advice before making any financial decisions. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.

Reproduced from the Tatton Weekly with the kind permission of our investment partners Tatton Investment Management

Who are Vizion Wealth?

Our approach to financial planning is simple, our clients are our number one priority and we ensure all our advice, strategies and services are tailored to the specific individual to best meet their longer term financial goals and aspirations. We understand that everyone is unique. We understand that wealth means different things to different people and each client will require a different strategy to build wealth, use and enjoy it during their lifetimes and to protect it for family and loved ones in the future.

Our approach to financial planning is simple, our clients are our number one priority and we ensure all our advice, strategies and services are tailored to the specific individual to best meet their longer term financial goals and aspirations. We understand that everyone is unique. We understand that wealth means different things to different people and each client will require a different strategy to build wealth, use and enjoy it during their lifetimes and to protect it for family and loved ones in the future.

All of us at Vizion Wealth are committed to our client’s financial success and would like to have an opportunity to review your individual wealth goals. To find out more, get in touch with us – we very much look forward to hearing from you.

The information contained in this article is intended solely for information purposes only and does not constitute advice. While every attempt has been made to ensure that the information contained on this article has been obtained from reliable sources, Vizion Wealth is not responsible for any errors or omissions. In no event will Vizion Wealth be liable to the reader or anyone else for any decision made or action taken in reliance on the information provided in this article.