Market Update: A dovish hawkish rate cut for Christmas

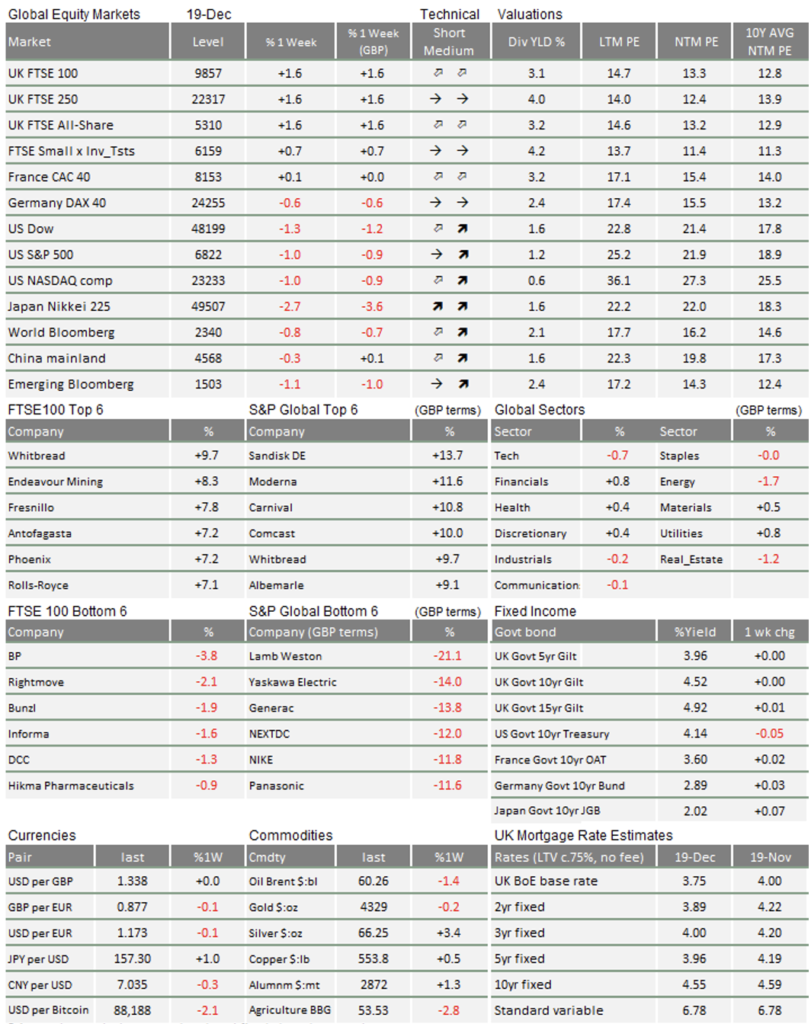

Last week had been the last week of liquid trading for 2025. The return of US economic data has sharpened the view that the US and other regions have had a soft patch.

Interestingly, that clarity has helped rather than hurt markets. Investors think the Fed will react to weakness which means there is not much likelihood of economic recession or profit decline. Equity investors have continued to be a bit unsettled but the main worry remains that very profitable companies are very expensive, especially if those profits are not used for share buybacks.

In the UK, long maturity bond prices and yields are stable but short-maturity bond yields have fallen (and so bond prices have risen). Why? Well, on Thursday, as expected, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) cut the Base Rate by 0.25 percentage points to 3.75% although the 5-4 vote was much tighter than expected. The minutes told us that the policy stance is only slightly restrictive now and any future easing will “depend on the evolution of the outlook for inflation.”

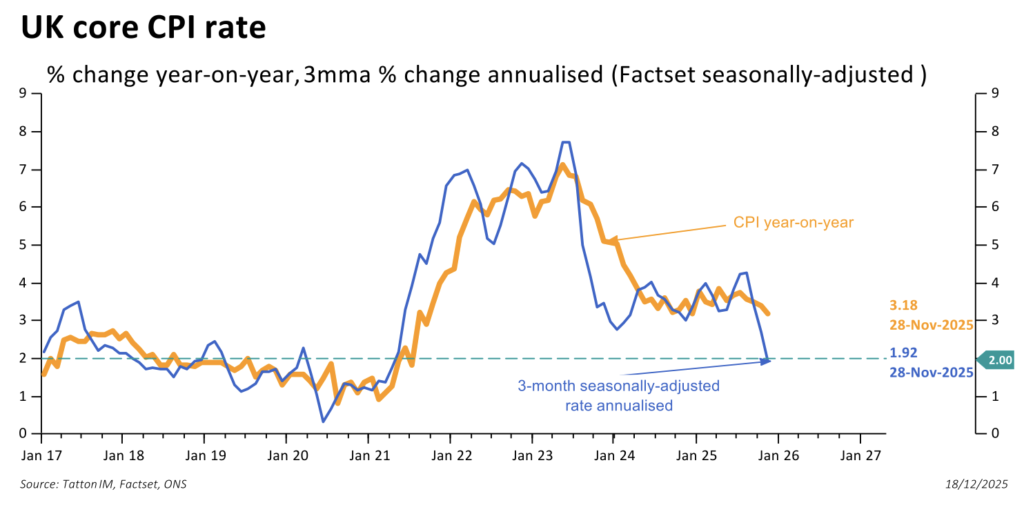

Is the MPC’s propensity to be hawkish a worry and if so why did the short yields decline which would be a sign that markets have become more certain about further cuts? A look at the data explains it: following the soggy UK employment data, this week’s consumer price inflation rate was lower than expected. The overall and core CPI year-on-year growth rates dropped to 3.2% versus the expectation of 3.4% year on year. While the rate is still above the BoE’s 2% target, the nearer-term core CPI growth rate has slowed to below 2%, and this has been helped by a slowing in service price rises. So, despite the MPC hawkish talk, markets see room for further cuts because inflation is falling as long as the MPC remains responsive to a softening economy further rate cuts are a reasonable expectation.

The graph above shows how the recent data indicates that the year-on-year inflation rate is on a downward path, partly because the UK’s employment tightness has eased, partly because the world’s economy has slowed into the end of the year.

The Bank of Japan faces quite a different domestic economy compared to most other central banks, in that it raised – not cut – rates by 0.25 percentage points to 0.75%. The consumer price inflation rate has risen to the levels of other developed nations, while interest rates have remained at very low levels. The yen actually slightly weakened against most other currencies, a sign that the central bank is not seen as overly hawkish over the medium term, even if it is currently raising rates. Tokyo’s November inflation growth rate was 2.7% year-on-year and unlikely to fall significantly as domestic businesses are displaying pricing power. We suspect Japan’s central bankers will watch these 2026 inflation dynamic like hawks and may still surprise markets.

In the US, this week’s flood of data included the employment report which was weakish (unemployment rose from 4.4% to 4.6%, with government layoffs surging), and culminated in Thursday’s US inflation report, surprising even more than the UK in its softness. November overall CPI rose by (the same as in Japan) 2.7% year-on-year, with core at 2.6% year-on-year. Both were 0.4% lower than expectation, a big difference.

As we said earlier, the return of economic information has revealed that the US has gone through another soft patch but it won’t be clear how much of this is attributable to the government shutdown itself (and November data quality is still being impacted since it only started to be collected from mid-month). When cutting rates last week, the Fed said further cuts from 3.625% would have to be justified by data – and this week’s wodge has led to expectations of a Fed Funds rate near 3% by the end of 2026.

And yet, equity analysts are not expecting economic weakness. The most obvious sign of this is that net margins (and analysts’ expectations thereof) are rising consistently across almost all of the developed world regions, even if this is a bit skewed by the inclusion of banks and other financials, whose margins are more volatile and say little about pricing power or productivity gains. Overall, analysts expect businesses to be able to maintain and even improve pricing power.

In the US, the expected earnings-per-share levels in twelve months’ time continue to rise very strongly (the last month has produced a 24% annualised growth rate), mainly because analysts have not adjusted down any of their strong 2026 forecasts. And, among the S&P 500 stocks, the stocks below the Magnificent Seven (the ‘S&P 493’) are seeing EPS growth estimates catching up to the top group.

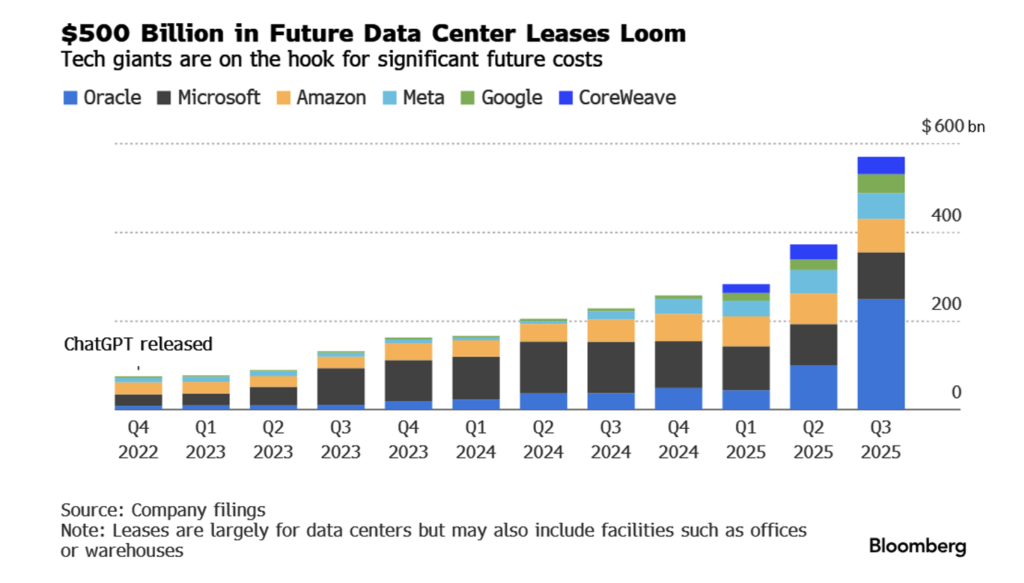

While tech stocks are still under some pressure, the pain is currently being borne by those trying to break open the Magnificent Seven clique – mostly Oracle and Broadcom. Oracle’s expansion issues continue; Blue Owl, the private equity and credit manager decided not to participate in the financing for (yet another) Oracle-led data centre in Michigan. These new data centres are not owned directly by the tech firms that institute them – rather, the sponsoring firms such as Oracle contract to lease the facilities for a long period, and money is raised against the value of that lease. Bloomberg has estimated the value of the leases to which the firms have committed in each quarter over the past three years:

Oracle’s share price has almost halved as the cost of financing has gone against it. Yet the attempt to be one of the dominant players in data could prove to be a winning strategy. Indeed, isn’t this the lesson that the Magnificent Seven has taught us over the past few years?

One ought not to be surprised if the cost of capital goes up if a firm keeps asking for more capital. The firm’s valuation, being the inverse of the cost of capital, should probably fall. The capital raised will be spent but it’s not clear who exactly will be the main beneficiaries. It could well be the other tech firms – circular financing may just be a way of saying that they have a near-monopoly on production. We therefore suspect that Oracle will do well from its strategy over the medium to long term, while in the short term it’s become the focal point of those who subscribe to the AI bubble talk, but perhaps do not focus much on the hard numbers of computing demand growth.

In our outlook for 2026, we say that there are good reasons to think that a broader range of companies will do well. Firstly, the AI capex spending is huge and will benefit many suppliers, especially in the US; secondly, Europe’s defence spending must be increased and quickly, which will benefit Europe’s suppliers; thirdly, the use of AI will add to productivity.

We can now add that the soft end to 2025 probably enhances the prospects for next year since that broad range of companies, consumers and governments will be helped if rates can fall a bit further. The benefits will flow over the course of next year but investors have started to buy into more cyclical stocks and that trend may be set to continue.

We cannot end without a comment on the great disruptor’s first year of his second term. Yes, President Trump is now completing the first year of his four, while having generated enough news to fill the full four years. He and his administration have attempted to move quickly and break things but that sense of revolution ought to give way to more stability at some point. Measures of political risk have subsided since the end of the US government shutdown.

But, as we reach the end of the beginning of Trump’s presidency, he would have hoped to have better approval ratings by now, and that probably means more policy initiatives and possibly more disruption next year. Progress on bank deregulation (which may spur Europe into similar action) is likely, and that would probably be market-friendly. He may be tempted to loosen fiscal policy substantially as we approach the mid-terms, which could turn into a double-edged sword for both bond and equity markets. And we should be aware that an unhappy Trump tends to seek enemies, and that can have impacts for erstwhile friends.

This week’s writers from Tatton Investment Management:

Lothar Mentel

Chief Investment Officer

Jim Kean

Chief Economist

Astrid Schilo

Chief Investment Strategist

Isaac Kean

Investment Writer

Important Information:

This material has been written by Tatton and is for information purposes only and must not be considered as financial advice. We always recommend that you seek financial advice before making any financial decisions. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.

Reproduced from the Tatton Weekly with the kind permission of our investment partners Tatton Investment Management

Who are Vizion Wealth?

Our approach to financial planning is simple, our clients are our number one priority and we ensure all our advice, strategies and services are tailored to the specific individual to best meet their longer term financial goals and aspirations. We understand that everyone is unique. We understand that wealth means different things to different people and each client will require a different strategy to build wealth, use and enjoy it during their lifetimes and to protect it for family and loved ones in the future.

Our approach to financial planning is simple, our clients are our number one priority and we ensure all our advice, strategies and services are tailored to the specific individual to best meet their longer term financial goals and aspirations. We understand that everyone is unique. We understand that wealth means different things to different people and each client will require a different strategy to build wealth, use and enjoy it during their lifetimes and to protect it for family and loved ones in the future.

All of us at Vizion Wealth are committed to our client’s financial success and would like to have an opportunity to review your individual wealth goals. To find out more, get in touch with us – we very much look forward to hearing from you.

The information contained in this article is intended solely for information purposes only and does not constitute advice. While every attempt has been made to ensure that the information contained on this article has been obtained from reliable sources, Vizion Wealth is not responsible for any errors or omissions. In no event will Vizion Wealth be liable to the reader or anyone else for any decision made or action taken in reliance on the information provided in this article.